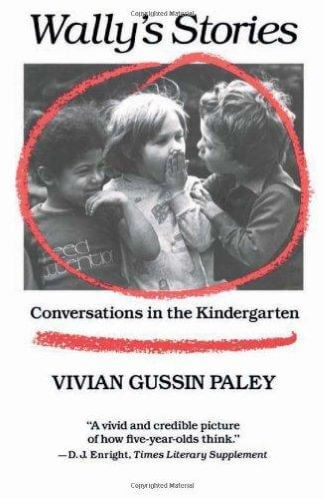

Wally’s Stories: Conversations in the Kindergarten

by Vivian Gussin Paley

Review by Linda Pound

Throughout her working life Linda Pound committed herself to improving the quality of provision for young children and families. She has worked in three universities and as an LEA inspector in London.

Book No: 2 – 1st published: 1981

The adult should not underestimate the young child’s tendency to revert to earlier thinking: new concepts have not been ‘learned’ but are only in temporary custody. They are glimpsed and tried out but are not permanent possessions.

Although Wally’s Stories was not the first that Vivian Gussin Paley wrote, this was the first of her books that I read. Now almost forty years later, it is still the book I wish I had written. Her capacity to not merely listen but to work at really understanding each child’s thinking shines through. Early in the book she writes: ‘you can write a book about thinking – by recording the conversations, stories and playacting.’ In fact she has written many such books, each without overt reference to theory, though this remains my favourite.

Paley’s curriculum is firmly based on the events confronting children in her kindergarten class on a day to day basis and on the stories they dictate and then act out in her classroom. She transcribes children’s conversations at the end of each day, so that she can reflect on how best to help them shape their conversations and how ‘to keep the inquiry open long enough for the consequences of their ideas to become apparent to them.’ She ends the book by outlining the silent pact she has made with the children. Using their play, their Storytelling and their Story Acting she promises…

If you will keep trying to explain yourselves, I will keep showing you how to think about the problems you need to solve.

This book is a springboard from which to explore storytelling in greater depth and is also a challenge to a teacher to reflect on how we can do more to enable this crucial aspect of child development.

It is worth noting that Paley’s writing, like her pedagogy, is very child-centered. Apart from the above quotes, she does not dedicate much of this book to statements on her opinions on storytelling, preferring to let the children speak for themselves. This writing style means reading the books feels intimate and intriguing; the reader gets to be a fly on the wall of Paley’s wonderful classroom.

If a reader was to approach this book hoping for an academic text full of theory and references it is fair to say they would not come away with what they were looking for. However, what they would come away with is a sense of how vast the possibilities are for child development in the act of Storytelling and Story Acting, (or Helicopter Stories).

I would highly recommend ‘a child’s work‘ to anyone who is involved in early childhood education, and anyone who hasn’t yet been lucky enough to have first-hand experiences of ‘the endless possibilities suggested by a magical tree and a little bird who has the keys to the kingdom.’

The trouble is that children do not confer legitimacy on the ruler. We can insist that the children repeat our ‘fact’ – this brings them our approval – but we cannot force-feed a concept before there is trust in the premise.

‘Temporary custody’ of concepts is not limited to mathematics – but encompasses social, cultural and linguistic issues. Paley maintains that her focus on ‘logical thinking and precise speech,’ starting with children’s magical solutions and fantasy is what will best prepare them for formal schooling.